by Juhi Mathur

The human mind is a complex entity in its own right, as it navigates myriad sensorial experiences and manifests itself through one of the most cherished human inventions: creativity. I have deemed ‘creativity’ as an invention, as it was born out of the human condition, as a result of all the experiences together. The driving force behind Rinku Choudhary’s artistic inventions is nostalgia which found its new home in creativity, it merged with her memories and her idiosyncrasies in a poetic manner. The word nostalgia has Greek roots, derived from the words nostos and algos, translating to the feelings of homesickness and pain, henceforth defining emotional and mental states which weave pain with a longing for home. It is an exploration of the intricate and often chaotic nature of human thought and visualising the ‘stream of consciousness’. It delves into the realm of random, recurring, and confusing thoughts that weave through our consciousness daily. The swirling patterns and fragmented imagery represent the labyrinthine journey of the mind as it navigates through a series of ideas and emotions.

Interestingly, in the late 18th and 19th centuries, both in the Western world as well as in the East, artists were reacting to the societal and cultural developments that rapidly changed the present circumstances. While the works of artists from the Romanticism movement epitomised nature and painted vast endless patches of green pastures, as experienced in the works of John Constable and J.M.W Turner, the 19th century in India saw artists and artisans working under British draughtsmen, documenting the natural terrain of the cities, forests and villages, capturing the bucolic charm of Colonial India – artists from Awadh and Patna school. It was a start reaction to the rapidly urbanizing world, ushered by the Industrial Revolution. Similarly, Rinku’s work is a reaction to the societal expectations thrust upon one’s shoulders, it is not a criticism of the demands and pressure which reverberate the life of an Indian woman, but a thesis on it, a form of introspection on life and how time defines the passing of it but it can never take away the impact of childhood memories and experiences. Her works showcase the world where humans are stripped of any pretence and left to face their true selves on a two-dimensional surface.

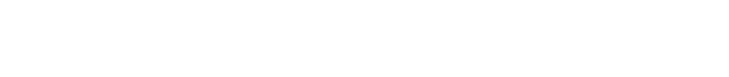

12 x 8”, Mixed Media on Paper, Image Courtesy: Art Incept

Growing up with her uncle and aunt in a big family, Rinku reminisces her childhood in the shades of art classes in school and musings at home about life and co-existence. Living in a joint family and not being able to explore the world after dusk, an imposition that was granted due to her gender, Rinku transformed her family members into subjects of her visual narratives; a way to understand the true human self. It became a central theme in her pieces – the depiction of an abstract home, surrounded by visual chaos in a place of comfort and familiarity. This juxtaposition highlights how our thoughts, no matter how disordered, are deeply connected to our everyday surroundings and experiences. The familiar objects and settings within the artwork serve as anchors, providing a sense of stability amidst the mental turbulence.

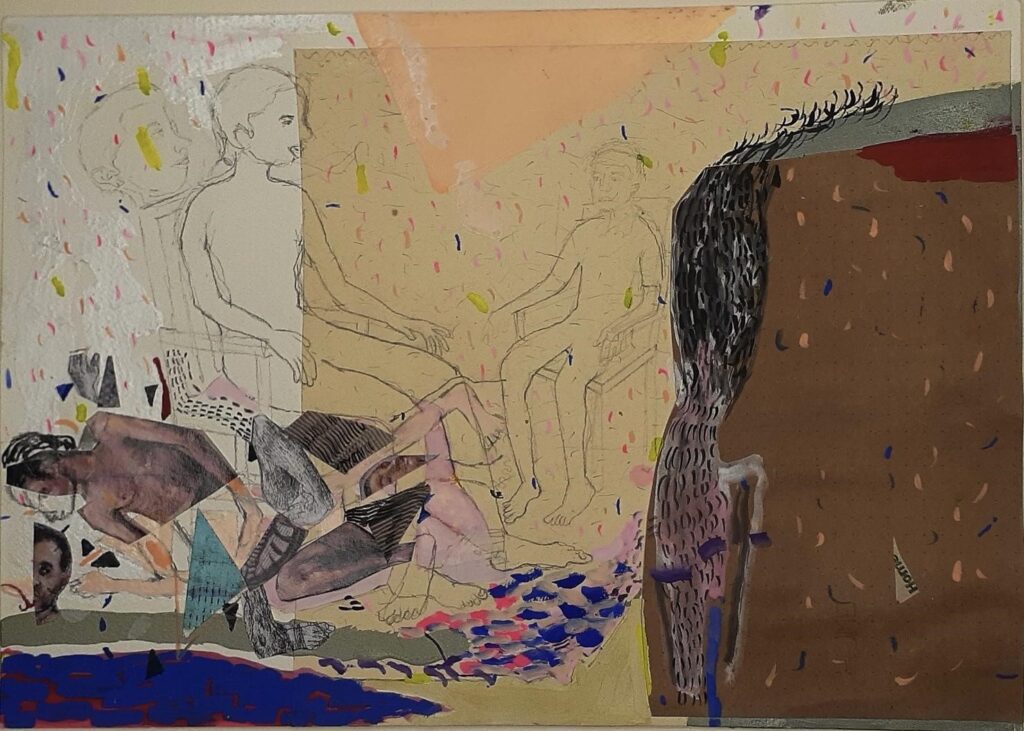

Art critic and poet Donald Kuspit, while understanding Mary Cassatt’s motivation and female gaze to paint the mother and child in most of her works while being unmarried herself, mentions the theory of true self, which was thoroughly studied by psychoanalyst Dr D.W. Winnicott. He talks about the formation of a false self that is created through our experiences during our formative years, and our true self is present as our unconscious self, which comes to life when it is given maternal care. In Rinku’s works, the creative process behind the various renditions of existence and isolation presents her true self, her actual identity and her emotional state. Through her figurations, she creates a “spontaneous gesture” which is alive and full of authenticity. Her paintings strip the subjects of any form of idealisation, as the static visages overlap each other. It is akin to a cacophony that is created due to overlapping voices during a conversation forming a visual collage and presenting those moments of family and human interactions through silent and chromatic compositions. This artistic expression is aligned with Dr. Winnicott’s theory where he observes that – “The spontaneous gesture is the True Self in action. Only the True Self can be creative and only the True Self can feel real. Whereas a True Self feels real, the existence of a False Self results in a feeling unreal or a sense of futility”.

Rinku’s figurations are dedicated narratives in themselves brimming with empathy for several generations of women around her, bringing forth cultural and societal connotations that are embedded in a woman’s life. The isolation and the solitude that is depicted through lone figures is a visual translation of the self-reflection that she went through during the pandemic when home became a space of enquiry for her. Her inner world and outer world collided as she began to unearth the layers of humanity, existence, and the identity of a woman in the grand scheme. She noticed the unchanged routines of many women in her life, they were still existing as wives, mothers, caregivers, and anchors in their domestic space. Rinku’s gaze turned them into subjects of her inquiry into the gendered nature of existence and its omnipresence during the pandemic, touching upon the complex politics of gender and emotional labour in the domestic domain, subtly touching upon the gender disparity.

In terms of formal composition, there are repetitive motifs of a chair and a woman sitting on that chair in a haphazard position, in some instances she is isolated, and in some she is surrounded by distorted human bodies, turning the scenario into a commentary on the symbolisms of leisure and power. Channelising her suppressed desires, thoughts and views through these pictorial compositions. The repetition of certain architectural settings and furniture showcases her process of connecting each work as a specific chapter in a visual narrative. Overlapping figures, linear drawings, juxtaposition of diverse objects, and animals like birds and dogs again connect us to Rinku’s true self. She discussed how these animal totems were derived from her childhood days – birds from her old home terrace in Delhi – 6 and her pet dog trace her nostalgia and her ability to present her cerebral world through images, she relives those memories and finds new meanings within them.

Creating this imaginary world that has imprints of real experiences within it, Rinku creates a vibrant panorama with a vast array of hues and shades that demand our attention. The bold lines and flat planes of colour dive into the modernist cubist tendencies that underpinned the compositions of Tyeb Mehta, where forms spoke to each other in poetic verses, where colours defined moods and mental patterns. Using a similar terminology, Rinku has empowered her subjects and her contemplative true self through the usage of colours that defy the naturalistic order of things, creating her visual vocabulary and distinctive universe.

Rinku’s insightful female gaze harkens back to domestic spaces created by Mary Cassatt and the otherworldly folkloric figurations of Arpita Singh. She has noted that her area of research and its visual treatment complement each other, her colourful visages draw the observer in, and on closer inspection, they incite a visceral response to the presence of gender disparities, to the isolation that woman feels, and the solitude that introspection commands – it encourages a newfound intimacy with knowledge of self. This reflective stance becomes more noticeable through the repetitive marks and dashes which seem to emulate the pointillist techniques of the French Impressionists, however, Rinku has infused these markings as abstract ideas and decisive emotive outlet, making her works more expressionist in nature akin to otherworldly creations of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. They carry sombre undertones, defined by the linear graphite drawings representing the artist’s melancholy and creative sensibilities, carrying a similar essence from the expressionistic drawings of Rabindranath Tagore; Rinku has specified these repetitive confetti-like brushmarks static in mid-air are a a way of finding a meditative medium through her artistic expression.

Her visual narratives chart through the terrains of existence and life of women through child-like and folkloric motifs, plunging into a fantastical world of intricately layered semi-representative figures which are juxtaposed against the totemic forms of varied fauna and household furnishings, manifesting a world where emotions and moods are signified through vibrant hues and markings. Rinku’s works are an avant-garde feminist inquiry into the condition of the contemplative self, trapped inside the man-made walls, while mind and soul etch the canvas with deliberate questions and inquisitions.

About the artist: Born in 1992, New Delhi, Rinku Choudhary studied painting followed by a Masters from College of Art, New Delhi. Her work deals with the recurring emotions and thoughts of daily lives. Rinku’s practice unravels her experiences in different domestic spaces, tinged with a hint of melancholia as introspection deepens, layering her compositions with fauvist flair. Rinku recently displayed her works at the MOMUS Museum, Greece, and was selected for the 62nd Lalit Kala Akademi National Exhibition of Art 2020-21. She is the recipient of the Shrishti Art Support grant 2020.