Shankar Tripathi

.

A flower does not announce its arrival; it germinates quietly, beneath the surface, negotiating darkness, pressure, and time. Badush Babu’s artistic practice, similarly, is sediment, detailing all that lingers, settles, and waits. His are drawings that unfold slowly, where growth and decay are not opposites but companions, moving together through matter, memory, and touch.

.

I. Seed

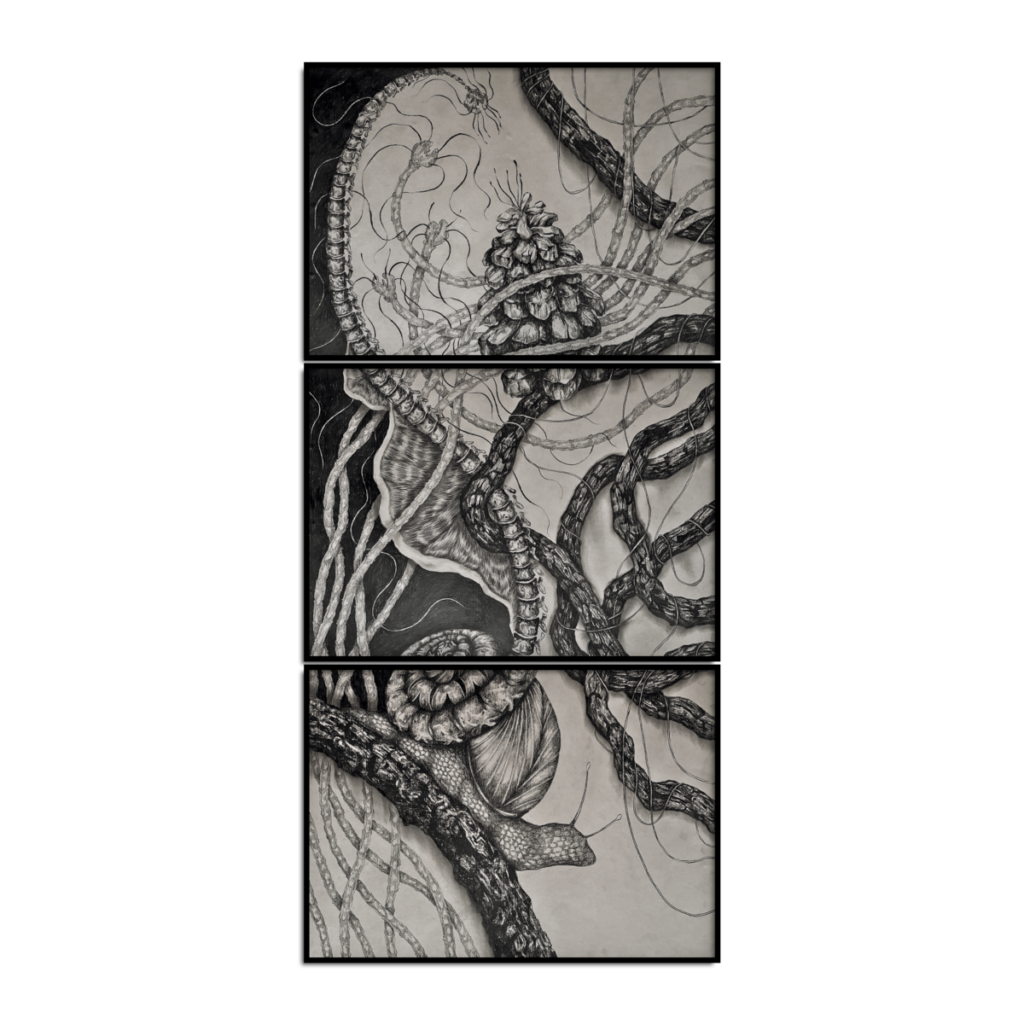

Born in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, Badush’s earliest encounters with art making were tactile and instinctive. As a child, he played with soot and residue—materials without form or permanence—unaware that these ephemeral gestures would later return as a central language of his practice. What Badush was impressed with was a sensation: the blackness that stains, the trace that refuses to disappear; an impression that remained with him dormant, like seeds pressed into soil, waiting for the right conditions to surface. Badush’s preoccupations—then, as they are now—were with materials that could register touch, accident, and atmosphere; a direction that allowed him to experiment with fumage and soot, opening a path where drawing became a site of accumulation, not just representation. It was here that charcoal emerged as a tool, as a lifeline, as a necessary extension of thought, capable of holding texture, depth, and the fragile residue of movement. Badush’s early works, most notably from the ongoing ‘Silent Stories’ series, however, were not overburdened with interpretation; instead remaining as acts of recording, as impressions gathered and left behind, until what followed was a conviction to look further, a desire to observe how pressure darkens, how friction erases, how scale can transform intimacy into immersion. Charcoal, with its capacity to be both precise and unstable, began to dominate the surface. The seed had found its soil.

.

.

II. Stem

Every growth encounters resistance. For the artist, this resistance arrived as an intimate personal loss, witnessed through the slow diminishing of his grandfather. As the body’s capacities gradually narrowed, the elder Babu’s attention turned, blossomed, outward—towards the garden, towards the natural world. There is something quietly resonant here with Henri Matisse, who, in the later years of his life, when painting became physically untenable, turned to collage (what he called ‘painting with scissors’), finding in cut paper a way to continue making work that was luminous, expansive, and full of joy. Gardening, too, emerged as such a gesture: a means of warmth and comfort, of bypassing limitation without surrendering vitality, of tending to life even while standing in close proximity to its finitude.

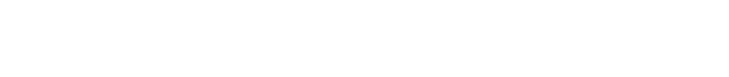

This left a lasting imprint on the artist, who in turn began tending to his mother’s garden. Badush found himself drawn into a space where grief did not demand language, permanence, or immediacy. Chaotic, dense, unruly the garden became both refuge and mirror, where plants crept and grew, and flowers appeared without announcement. There was no order imposed, yet no chaos perceived; what emerged instead was a quiet logic of coexistence. It was here that flora entered his work, metaphoric as well as illustrative. Human life—with its fear, anxiety, loneliness, and transience—found resonance in vegetal cycles. Growth did not erase decay; decay did not negate beauty.

The melancholic origins of this imagery, however, transformed quickly into a recognition of resilience and renewal. The flower, in bloom, carries the certainty of its own wilting, yet this does not diminish its intensity. Baudush’s work began to lean towards such optimism; a visual acknowledgment of a healing that occurs alongside vulnerability. His draughtsmanship found companionship in fallen flowers, dried leaves, and dead insects—objects often offered by friends or gathered from the ground—objects which became extensions of his visual vocabulary. These fragmented trophies were reminders of a life, our life, that persists through shedding, through leaving things behind. Badush’s artworks have slowly evolved into a form of care.

.

III. Bloom

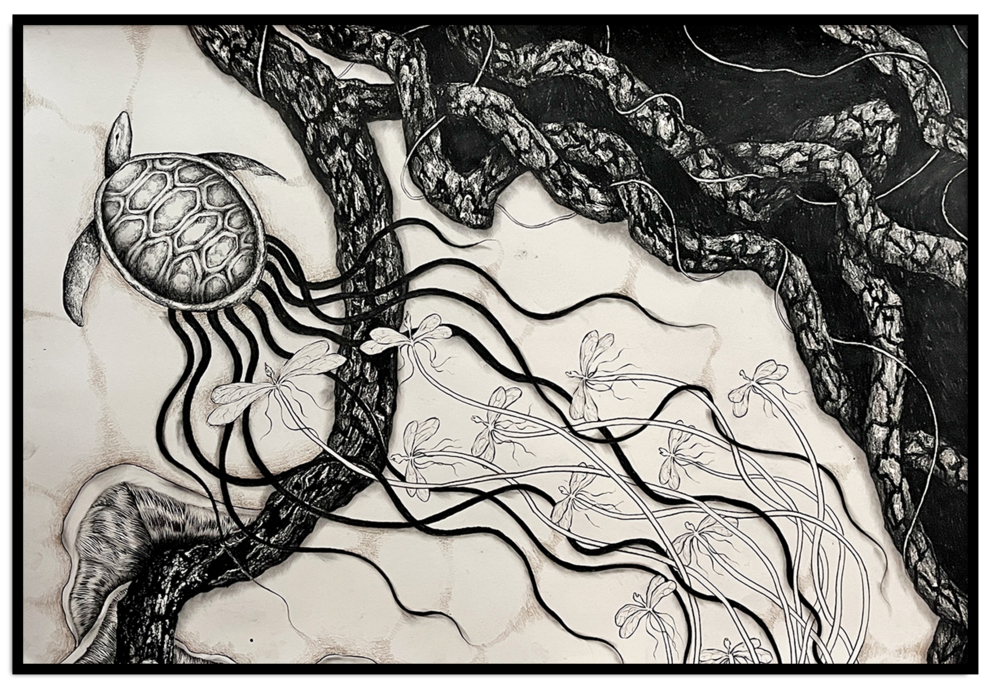

Badush’s botanic art has become embodied with charcoal; a material, after all, born out of transformation—wood reduced by fire, life translated into carbon. In the artist’s hands, it carries its own philosophy. It stains irrevocably, yet remains fragile; it can be erased, but never fully undone. It is at once growth and ash. Badush’s artistic process, moreover, mirrors organic expansion. Beginning with a single sheet, the work grows outward as the hand moves, as the image asks, demands space. Additional sheets are attached fluidly, allowing the drawing to find its own perimeter. There is no predetermined boundary; completion arrives when the work exhausts its path. This additive gesture echoes vegetal growth, with branches extending outward, roots spreading downward, and forms responding to pressure rather than plan. Charcoal, moreover, allows the artist to think intimately as well as expansively. Minute details—veins of leaves, textures of bark, the softness of decay—can be magnified without losing their softness, their fragility. The surface becomes a site of accumulation, where Badush’s hand builds density and time becomes visible. The artist speaks of feeling “one with the charcoal,” an intimacy that is both emotional and corporeal. The medium absorbs breath, sweat, hesitation, becoming an extension of the body, carrying within it the residue of an experience lived.

Literary and cinematic influences further deepen this material inquiry. Reading Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka, Badush meditates on fragility and transformation, on how the weight of an emotion can reshape the body itself. Similarly, Khasakkinte Ithihasam by O. V. Vijayan offers a landscape to the artist where myth, humour, and decay coexist, where land becomes a sentient participant in human suffering. This is similarly felt in the films of Abbas Kiarostami, where terrain holds the weight of the narrative, reinforcing the artist’s attention towards the environment as protagonist first, backdrop second. Even childhood memories return transformed. Butterflies once handled with innocent curiosity, their wings disintegrating at the slightest touch—reappear as symbols of beauty inseparable from fragility. Snakes shedding their skins in the garden become potent metaphors of healing through vulnerability: moments of weakness that enable renewal. In these observations, Badush locates a quiet ethic of attention, where looking becomes a form of listening.

.

.

IV. Wilt

More recently, human figures have entirely receded from Badush’s works. What began as a figurative enquiry has pivoted toward the non-representational, towards a floral landscape that has become a carrier of multiple meanings. This representational absence, however, is not a negation but trust: a trust in the work to speak for itself. In Badush’s works, the human presence lingers implicitly, asking a persistent question lying at the very heart of such works: where do we go to heal? The artist repeatedly takes us to the—his, everyone’s—garden; an idyllic environment, irrevocably transformed by the notion of healing. This geography of coexistence, where insects interact, snakes pass through, and plants overtake space, is where life continues without hierarchy, offering a model of endurance that does not rely on control, but on an even more powerful action: of letting go. In this garden, we are increasingly made aware of movement; drawing, here, negotiates translating a three-dimensional experience, a transcendental feeling, onto a two-dimensional plane.

Badush’s artworks rest on the legacy of artists such as William Kentridge, Shanthamani Muddaiah, and Prabhakar Pachpute—not merely for their use of charcoal, but for their ability to transform one material into another, one state into its opposite. In their work, as in the artist’s, the medium is never static; it is always becoming.

Like a flower at the end of its cycle, Badush’s drawings do not insist on permanence. They accept erasure, smudging, fading, as natural as the breathable air his plants photosynthesise. And in this very acceptance lies their strength. It is a strength of acknowledging what remains: the trace of an image having been—of having grown, bloomed, and wilted with attentiveness. Badush Babu’s practice does not seek to arrest time. Instead, it aligns itself with time’s quiet labour. In charcoal and garden, in soot and memory, he offers a way of seeing where decay is not an ending, but a condition of possibility. The seed falls back into the soil, and somewhere, already, something else is beginning to grow. For now, the soil holds.